The first time Shalene Gupta had a doctor suggest that she might have a mood disorder related to her menstrual cycle, she was indignant.

“Another doctor and I were like, ‘No. That’s really sexist,’” said Gupta, who graduated in 2009 from the Johns Hopkins University with degrees in creative writing and psychology, and now lives in Boston.

Looking back, Gupta wonders what would have happened if she hadn’t dismissed the doctor’s idea. Maybe it wouldn’t have taken her so long to be diagnosed with premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or PMDD. It is a menstruation-related mood disorder that, before Gupta received treatment, caused her to have monthly depressive episodes where she hurt herself, thought about suicide and sometimes attempted it, and had vicious, explosive fights with her partner.

But Gupta has empathy for her younger self. Patients wait an average of 12 years to receive an accurate PMDD diagnosis, according to unpublished survey data from the International Association for Premenstrual Disorders, an advocacy and peer support organization. The disorder wasn’t added to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders — the handbook that guides mental health diagnosing practices in the United States — until 2013.

When Gupta was diagnosed, her instinct was to avoid talking about it, despite her relief at finally understanding her monthly spirals. But stigma around the disorder and delays in diagnosis are why she instead ran in the opposite direction. She wrote a book about it.

“I could not believe that it had taken me until the age of 30 to get a diagnosis,” Gupta said. “I lost a relationship. I knew, probably, if I didn’t get help, I would probably end up losing another relationship, or at least severely damaging it.”

“I was just like, ‘I don’t know how many other people are going through the same thing.’”

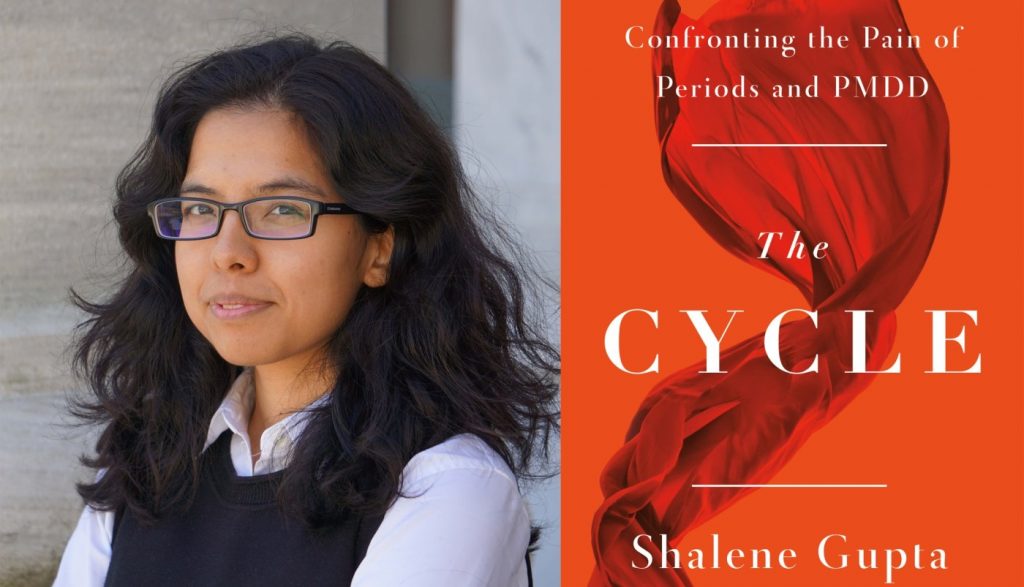

Gupta’s book, “The Cycle,” will be published Tuesday by Flatiron Books, a division of Macmillan Publishers. It contains descriptions of self-harm, suicidal ideation and intimate partner abuse.

It tells the controversy-laden story of how PMDD became a legitimate diagnosis and includes testimonies from people living with the disorder and researchers studying it. In a searing description of what it is like to live with an undiagnosed mental health condition, Gupta also shares her experience with PMDD and her long road to diagnosis and treatment.

“The Cycle” is Gupta’s second book, and the first she wrote by herself. As someone who started dreaming about writing a book when she was a child growing up in Minnesota, Gupta said Hopkins’ creative writing program — one of the oldest in the country — gave her permission to take that goal seriously.

“I still remember the first day of class freshman year,” she said. “Our TA [teaching assistant] sat us down and he was like, ‘You may have been good writers in high school, but your competition now is T.S. Eliot.’”

While there are other books on the market about PMDD, “The Cycle” will be among the first from a major publishing company. It features interviews with Maryland experts, including Liisa Hantsoo at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Dr. Peter Schmidt at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda.

The psychiatric association’s manual lists criteria for the symptoms a woman must experience — including depression, anxiety and increased mood swings — to be diagnosed with the disorder. The handbook also requires those symptoms to be so severe that they cause a woman distress or interfere with her work, education or relationships. Doctors typically have women keep track of their symptoms for two menstrual cycles before they consider a PMDD diagnosis.

Researchers estimate that PMDD affects between 3% and 8% of those who menstruate and are of reproductive age. Even more people experience another menstrual mood disorder called premenstrual exacerbation, or PME, where menstruation worsens their existing mental health disorders, such as anxiety, depression or an eating disorder.

While a menstrual cycle can range from 21 to about 35 days and still be considered healthy, the average cycle is 28 days. It can be divided into two phases: the follicular phase, which begins when a woman starts bleeding to shed an unfertilized egg, and the luteal phase, which starts when her ovaries release an egg.

For both menstrual mood disorders, symptoms surface during the luteal phase, when the hormones estrogen and progesterone increase in the body to thicken the lining of the uterus, then decline if there’s no fertilized egg present. Women with PMDD see their symptoms disappear when their cycle returns to the follicular phase.

Researchers have found that women with PMDD typically have normal levels of hormones, but have abnormal mood reactions to those hormone changes that occur during the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle. Schmidt and other scientists are trying to understand why that happens.

While awareness of the disorder has improved, Schmidt said he still hears from patients who struggle to get a diagnosis or whose symptoms are dismissed by their doctors. In general, he said, the country has a long way to go in removing the stigma around mental health issues.

“Depression is probably one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the world, but you don’t see a lot of press about depression as you would, say, cancer or heart disease or diabetes,” said Schmidt, who leads the National Institute of Mental Health’s behavioral endocrinology section and is one of the most prominent researchers in the PMDD field. “We all feel a little more comfortable when there’s a blood test or something physical, as opposed to involving the mind.”

Stigma, however, is just part of the story of why it took so long for PMDD to be included in the psychiatric association’s manual.

Since the 1980s, people have questioned the legitimacy of the diagnosis and wondered whether it is another example of the male-dominated medical field pathologizing women’s bodies. The mood swings some women experience while menstruating have long served as the butt of jokes and justification for why women shouldn’t hold political office or other powerful positions.

“The moment anyone’s going to say, ‘Periods are linked to mental health,’” Gupta said, “the knee-jerk reaction is, ‘No. This is the establishment making something up to hold women back.’ It’s completely understandable — except there’s a proportion of us who really do suffer and find treatment evidently beneficial.”

Hantsoo, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, said that if more doctors and medical professionals learned about PMDD and other women’s health conditions in medical school, it likely would be much easier for patients with the disorder to get diagnosed and treated.

Women with PMDD are sometimes misdiagnosed with other mood disorders like bipolar disorder or depression. This prevents them from getting the care they need, since the treatments for mental health conditions are different, Hantsoo said. Getting a diagnosis is also important for women to understand how PMDD has affected their lives.

“Finally having a name to put on it and saying, ‘OK, this is what this is,’” she said, “can be really helpful for people just in terms of their own processing of what they’re experiencing around these symptoms.”

For Gupta, it’s hard to overstate the power her diagnosis had on her life. Today, she wears a ring that measures her basal body temperature and tells her when she is ovulating. She takes fluoxetine — an antidepressant marketed as Prozac — from the first day she ovulates until her follicular phase begins.

She’s married to a man she adores. They have occasional arguments, but their partnership isn’t marked by the rage-filled battles of Gupta’s previous relationship. Overall, she feels like she now has more space in her brain. It’s easier to be present and laugh at little annoyances.

While she didn’t start writing “The Cycle” to process her experience with an undiagnosed mood disorder, that’s what it became.

“In some ways, writing the book for me was about narrating the story of the change, the shift in identity for myself,” she said, “of going from ‘bad person’ to ‘person who needs help.’”