Here’s how many Americans picture the average student borrower:

His name is Brad. He matriculates at a university that charges tuition and fees far beyond his means; he majors in postmodernist literary theory or queer studies; Brad’s classes aren’t demanding so he has plenty of time to attend rallies promoting socialism and Palestinian rights.

After four years — or five or six — Brad leaves behind keg parties and football games and graduates with a useless degree and a staggering five- or six-figure debt that he has no capacity to repay.

This isn’t a small problem. Student debt exceeds $1.7 trillion, more than Americans’ total credit card debt. The average debt is $38,000, and some students owe hundreds of thousands. Many pay a significant portion of their income toward this debt for decades, putting off getting married, having children or starting businesses.

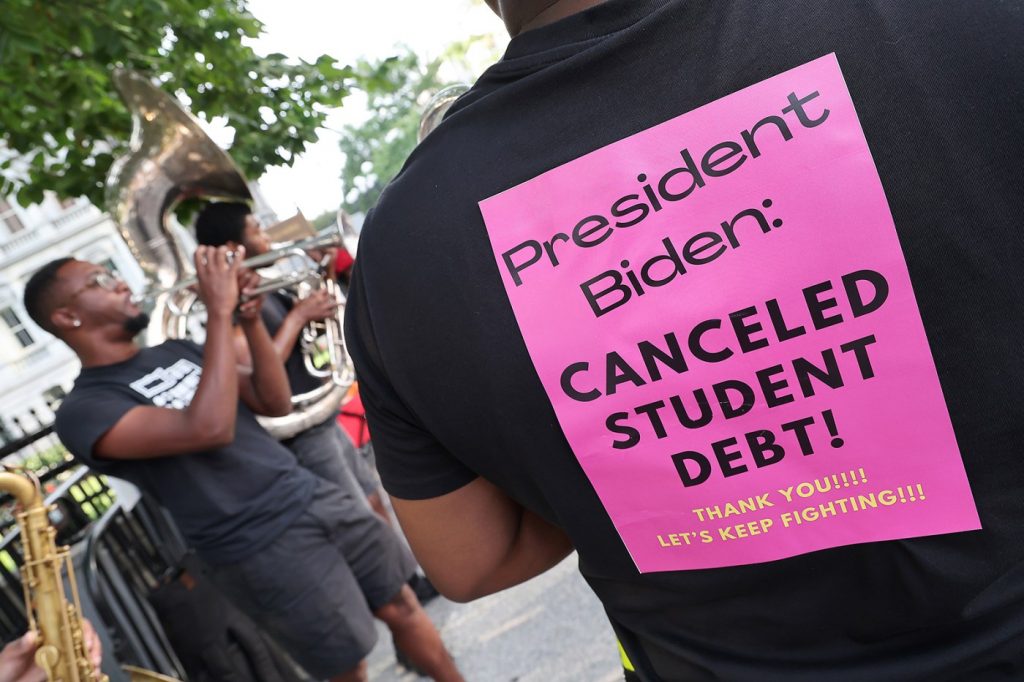

President Joe Biden has proposed forgiving some debt, but he has met considerable resistance. In fact, former president Donald Trump last year expressed feelings shared by millions of Americans: Forgiving student debt is “very unfair to the millions and millions of people who paid their debt through hard work and diligence; very unfair.”

Putting aside the fact that Trump has himself declared bankruptcy six times and has a reputation for stiffing contractors, he has a point: People who take out loans should pay them back. Of course.

But consider a couple of points in defense of student borrowers:

First: One semester decades ago, the University of Texas at Austin charged me less than $300 for nine graduate hours. Thanks to a combination of the G.I. Bill, Pell grants and work, I left the university with a postgraduate degree and zero debt. None.

This is an inconceivable fantasy for many modern students. It reflects our society’s growing tendency to regard a college education as a private good rather than a public good, which allows us to rationalize well-documented efforts to push the costs onto the student rather than the taxpayer. Many students, therefore, simply must borrow in order to go to college.

Second: An unforgiving attitude toward student borrowers doesn’t give them sufficient credit for the investment of time and energy required to complete a college degree.

My attitude toward students is probably colored by 35 years of teaching college freshmen, mostly at a large community college. My college had excellent facilities, but there were no luxurious dorms or gourmet dining halls, no fraternities, football teams or well-connected alumni. Forty percent of students attend such colleges.

Many of my students were smart and capable. Their average age was 27. Some had been in the Army. Many had families. Nearly all of them had jobs, often full-time. Rather than keg parties and football games, their distractions were family, work and finding a way to pay for their educations. In short, at my college there were no Brads.

In fact, Brad is a caricature that serves a cynical take on higher education. Annalisa, on the other hand, was a real person, a student who always sat in the front row of my freshman comp class 13 years ago. She said very little, but she did her work, and she showed every prospect of passing the course.

She played the clarinet and loved art and cats. The monsignor of her parish said that she was “just a really good kid.”

Related Articles

Klein: Biden finally figured out how to sell his own record

Editorial: California should reject AT&T bid to shed landlines

Walters: California school budgets plagued by enrollment declines, absenteeism

Blow: The war that will haunt Democrats through the campaign

Opinion: Past victories to protect queer kids at school aren’t enough

But she kept falling asleep in class. I never called her out because I’d seen firsthand how hard college students work, on their courses, in their jobs and in just living their lives. She wasn’t the first student to fall asleep in class.

But one day, she lost control of her vehicle on the way home from class, overcorrected, fishtailed and rolled over several times. She didn’t survive. She was 18. Maybe she fell asleep at the wheel.

Of course, I don’t know why she was so sleepy. Still, I’ve often wondered whether, if she had lived in a society that was more generous with helping young people improve themselves, Annalisa would now be a teacher or nurse, doing her best to improve the society in which she used to live.

John M. Crisp is a Tribune News Service columnist. ©2024 Tribune Content Agency.