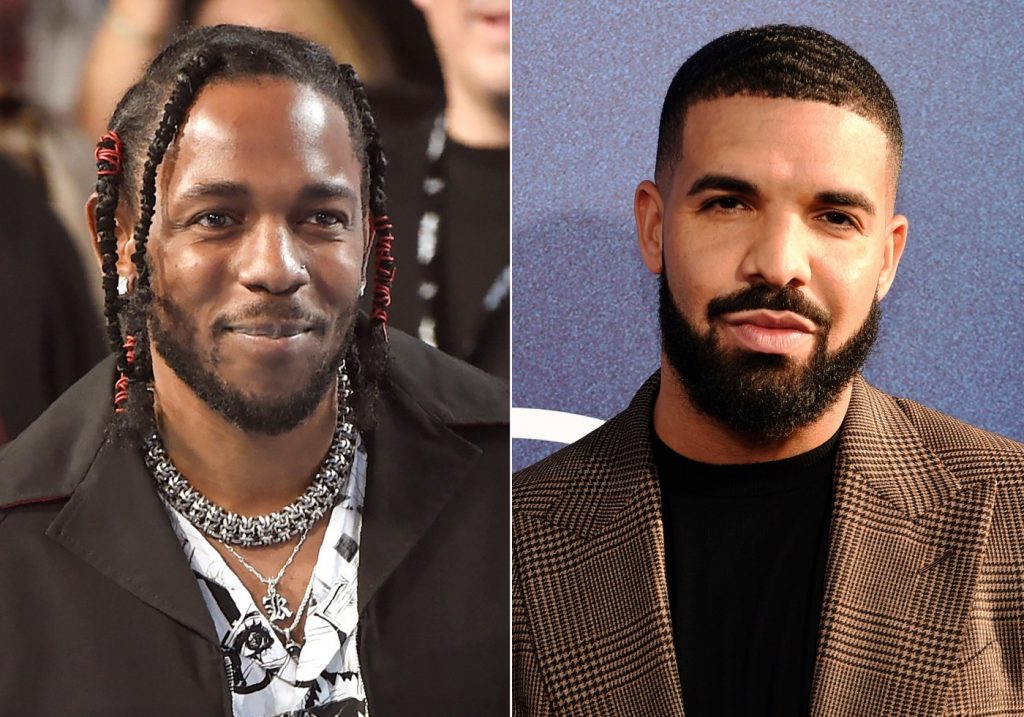

How did Oakland find itself in the middle of hip-hop’s “great war” — the breathless, vicious feud that fascinated the public as it raged this past month between Drake and Kendrick Lamar?

In the show-stopping single “Not Like Us,” which last week debuted at the top of the Billboard Hot 100 chart, Compton native Lamar suggested that a future Drake concert in Oakland would be the Toronto rapper’s “last stop,” implying Drake was no longer welcome here.

That’s because Drake, in a previous diss track targeting Lamar, employed artificial intelligence to imitate the voice of late legend Tupac Shakur, a controversial move that led Shakur’s family estate to threaten legal action.

Members of the local hip-hop scene aren’t surprised the town was thrust into the drama, given the city’s long legacy of contributions to the genre. But they aren’t sure what to make of Oakland’s depiction as a hub of retribution and violence — a dated reference in a city where legacy hip-hop artists spend most of their time investing in the community.

Idle threats are a common — and mostly unserious — feature of any rap beef. But would Drake really be met with violence in Oakland? The answer to that question among both older and younger generations of the city’s rap scene is, unequivocally, no.

“When it comes to ‘opps’ music — shooting your neighbors and whatnot — we’ve reached a point where we don’t want all of that,” said Daghe Digital, a producer and DJ who grew up in West Oakland and has worked with a number of hip-hop artists. “The young rappers here are heavily introspective.”

Many of the city’s legacy artists, meanwhile, are busy with pursuits outside the rap game.

Terry Butler, a.k.a. Mr. Community, transitioned a career that began with producing records for his high-school classmate Too $hort — the Oakland native who used to sell his albums from the trunk of his car in the ’80s before releasing a string of multi-platinum records in the ’90s — to now running music events for Oakland youth.

A sign for Too $hort Way is seen along Foothill Boulevard and High Street in Oakland, Calif., on Monday, Dec. 13, 2022. Too $hort Way was officially dedicated in honor of the Oakland rapper Too $hort, born Todd Anthony Shaw, on Saturday. (Jane Tyska/Bay Area News Group)

“Oakland now is different from what it was; there’s less of a foundation of hip-hop here now,” said Butler, who also produced music for Destiny’s Child and Alicia Keys. “But nobody from outside (the town) can decide what we do here.”

East Bay legend Mistah F.A.B., who now owns the clothing store Dope Era on Broadway, was most notable for repping the Golden State Warriors during their waning championship years in Oakland. He popped up last fall at the campaign launch against the recall of Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price.

The town’s shifting demographics amid an influx in recent years of wealthier transplants make it more difficult for most to imagine Drake would actually face retribution if he returns to Oakland, where the artist hasn’t played a concert since 2018.

Rappers E-40, from left, Too Short, Mistah F.A.B. and G-Eazy perform during halftime of Game 6 of basketball’s NBA Finals between the Toronto Raptors and the Golden State Warriors in Oakland, Calif., Thursday, June 13, 2019. (AP Photo/Tony Avelar)

His tour last year stopped twice at the Chase Center in San Francisco, but not in Oakland — another sign that Oakland’s foundation of being the Bay Area’s hub of the genre might indeed have been displaced.

Oakland has given birth to new artists who are eager to carry on the tradition. But social media has granted a younger generation boundless access to the world’s hip-hop offerings. West Coast artists no longer appear unified against opponents from the opposite coast. Or, in this case, Canada.

“Drake has a lot of respect for the Bay Area,” said Jacky Johnson, who helps coordinate Town Up Tuesday shows on Broadway. The concert’s latest edition this week is expected to feature Too $hort.

Daghe, the local producer, said Oakland’s “got love” for Drake. Another up-and-coming Oakland-based producer, Ovrkast, co-produced two tracks on Drake’s last studio album.

But the cultural pride in Oakland identified by Lamar, the trope that persists around town in cars booming with West Coast rap and murals of hip-hop legends, remains resonant.

It’s what made Oakland a special place to Shakur, the child of Black Panthers who was born in East Harlem and raised partly in New York, Baltimore and Marin City before becoming synonymous with Southern California.

Oakland, CA January 7, 1992 – Tupac Shakur. (Gary Reyes / Oakland Tribune Staff Archives)

In video of a 1993 interview, Shakur jolted upright at the mention of Oakland’s name and quickly began explaining why the town imbued him with so much “feeling” that simply didn’t exist in other cities.

He would rave about how his heart belonged to Oakland for the rest of his career, before his murder three years later.

Some of the city’s newer generation has leaned into wholesome messaging. In one of his many odes to the region, local rapper Loove Moore declared on “All I Really Want”: “We got hella talent in the Bay, and we ain’t gon’ let no hate get in the way.”

To Councilmember Carroll Fife, who last year built a relationship with Shakur’s family while organizing a local street renaming after him, all the negativity in Lamar and Drake’s “great war” serves mostly as a distraction.

“If Tupac were here, I do believe he’d be talking about Haiti and Congo and Palestine,” Fife said, referring to large-scale violence in all three regions. “I’m really tired of (the feud), to be honest. Can’t we just heal as a community?”

Randy Moore, of Los Angeles, poses beneath a new sign during a street renaming ceremony for Tupac Shakur in Oakland in 2023. A stretch of street in Oakland was renamed for Shakur, 27 years after the killing of the hip-hop luminary. A section of Macarthur Boulevard near where he lived in the 1990s is now Tupac Shakur Way, after a ceremony that included his family members and Oakland native MC Hammer. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

But many, including Fife, agree the beef has produced some of both artists’ best music and reaffirmed hip-hop’s core tropes: competition and confrontation. Those mediums traditionally offered “an alternative to violence,” said local artist DJ Torman Jahi.

“In a rap battle, you may lose, but no one loses their lives,” Jahi, a curator of the city’s hip-hop history at the African-American Museum and Library at Oakland, said in a direct message.

The balance between trash talk and real threats has helped harbor Lamar and Drake’s mutual disdain within the realm of entertainment, instead of something more sinister. Oakland’s artists, for their part, want it to remain there.