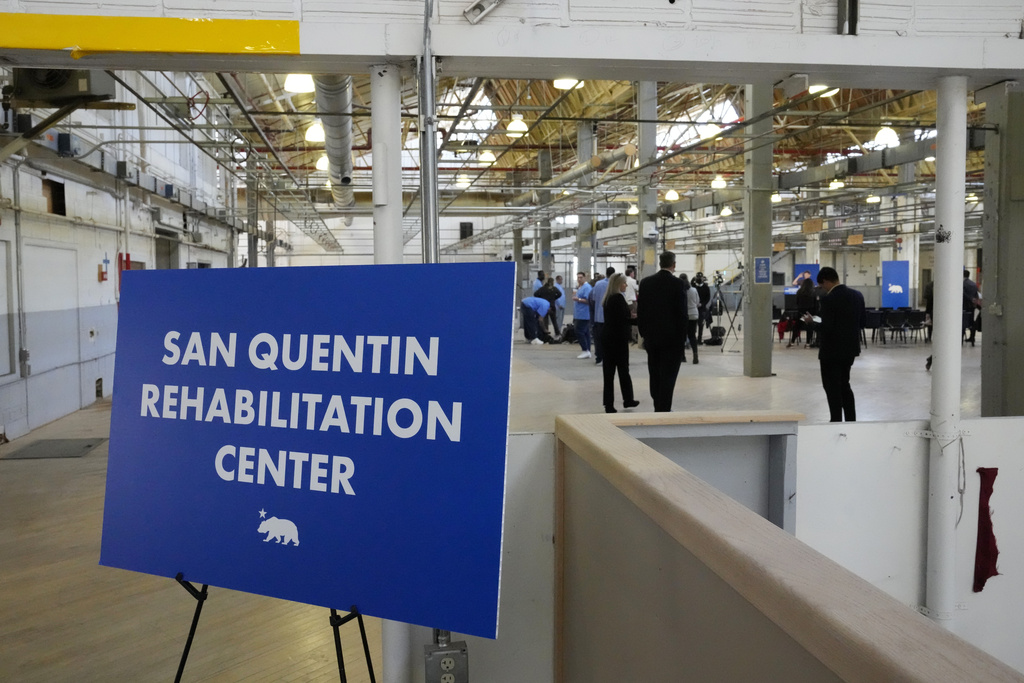

A first-of-its-kind orientation inside the San Quentin Rehabilitation Center last month helped illuminate what California can do to keep its prison population decreasing if lawmakers approve a budget cut that would close dozens of housing blocks statewide.

The recent event, hosted by the People in Blue, a special incarcerated committee working to change the culture of California’s prison system, comes at a time when Gov. Gavin Newsom wants to close 46 housing blocks in 13 different prisons to save an estimated $80 million a year.

Almost 3,000 people waited in line to enter a gymnasium and other locations where they were able to meet with dozens of incarcerated facilitators and self-help group volunteers from outside communities. The goal was to take a more active role in pursuing rehabilitation and healing.

“This needs to happen more often for youngsters coming here,” said L.L. Romero, a correctional officer who works with The Last Mile coding program. “It would help if everyone participated to help build a bond of communication, recognition, respect and relationships. We need to make a change.”

This event promoted TPIB’s so-called Linear Rehabilitation Model proposal, which was first presented to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation last fall.

“What many people don’t realize is participating in rehabilitation while in prison is not mandatory,” said TPIB president Arthur Jackson. “Incarcerated people don’t have to participate in any particular rehabilitation programs, and don’t have a right to any particular programs.”

Under the group’s rehabilitation plan, incarcerated individuals would enter the prison system and meet with a team of mentors, such as a custody officer, mental health worker and peer mentor, for example. This team will meet newcomers where they are, and help them develop goals for dealing with their trauma, substance use, gang affiliation and other types of issues before they’re released.

“People in prison should participate in rehabilitation,” Jackson said. “We should have a human right to rehabilitation and healing. A visual roadmap to rehabilitative success should be created for each individual entering into the system.”

Under California’s penal code, “the purpose of incarceration is rehabilitation and safe and successful reentry back into the community.”

CDCRs core values, expressed in its strategic plan, include empowering incarcerated individuals to transform their lives and providing unique programming opportunities so that they have a solid foundation when they return to the community. This requires creating safe spaces for incarcerated individuals to learn and thrive.

Today’s political climate contrasts the 1990s when Gov. Pete Wilson enacted tough-on-crime laws that essentially converted California prisons to human warehouses. The prison population peaked in 2006, causing essential services for prisoners to almost collapse. Officers suffered PTSD from dangerous, overcrowded conditions.

Related Articles

San Quentin inmate actors lean into notorious Shakespeare play

Feds face trial over reports of abuse at FCI Dublin

Opinion: California’s budget can’t afford to maintain empty prison beds

At East Bay federal prison tainted by sex-abuse scandal, all of the prisoners have been cleared out

Editorial: Dublin women’s prison closure rife with abuse and court secrecy

The population is currently 93,000 and still too large for the state to meet the rehabilitative needs of all prisoners. California’s prison footprint must decrease to accomplish the mission.

Most California prisons don’t have the rehabilitative infrastructure that San Quentin does. But if CDCR utilizes officers as sponsors and allows incarcerated people to act as facilitators, it can give other prisons a taste of San Quentin at no additional cost to taxpayers.

While closing 46 housing blocks may not save much money in the short term, enhancing rehabilitation programming can help population numbers continue to fall and eventually lead to five more prison closures, as the Legislative Analyst’s Office recommends.

It currently costs $132,860 per year to house each incarcerated individual. This cost will continue to rise with people leaving prisons in the same condition they entered it — unless access to rehabilitative programs is improved.

Steve Brooks is an award-winning incarcerated journalist who resides at San Quentin and works at San Quentin News. He wrote this column for CalMatters.