Public health experts in California are warning of a growing threat, concentrated in the San Joaquin Valley but spreading farther into the state.

That threat is coccidioides, a fungus that is primarily found in the southwest and western parts of the country. The illness it can cause, called Valley fever, or coccidioidomycosis, has notably increased in California this year, compared to previous seasons.

The number of cases reported to the state health department from January to June are about 60% higher than in the same time period the last two years, from around 3,500 in 2022 and 2023 to 5,500 this year. And experts say climate change is contributing to the increase.

The disease is caused by the fungus, called “cocci” for short, which lives in certain types of soil and dry environments. The symptoms can be similar to the flu and COVID: fever, cough, shortness of breath and sometimes a rash.

The fungus continues to grow as a threat in California and the western part of the country. Arizona is the other state that reports significant numbers of Valley fever cases each year, with the desert state historically reporting more cases each year than California.

While year-to-year fluctuations can be greatly influenced by the weather, “I think the increase over time is based on climate, i.e. global warming,” said Royce Johnson, medical director of the Valley Fever Institute in Kern County. And Johnson is among many experts who says climate change is making the situation worse.

In a paper published in 2019, researchers estimate that by 2100, “the area affected by Valley fever will more than double and the number of people who become sick will increase by 50%” using a climate model mimicking a ‘high’ warming scenario. And the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found a correlation between increased dust storms due to climate change and an increase in cases.

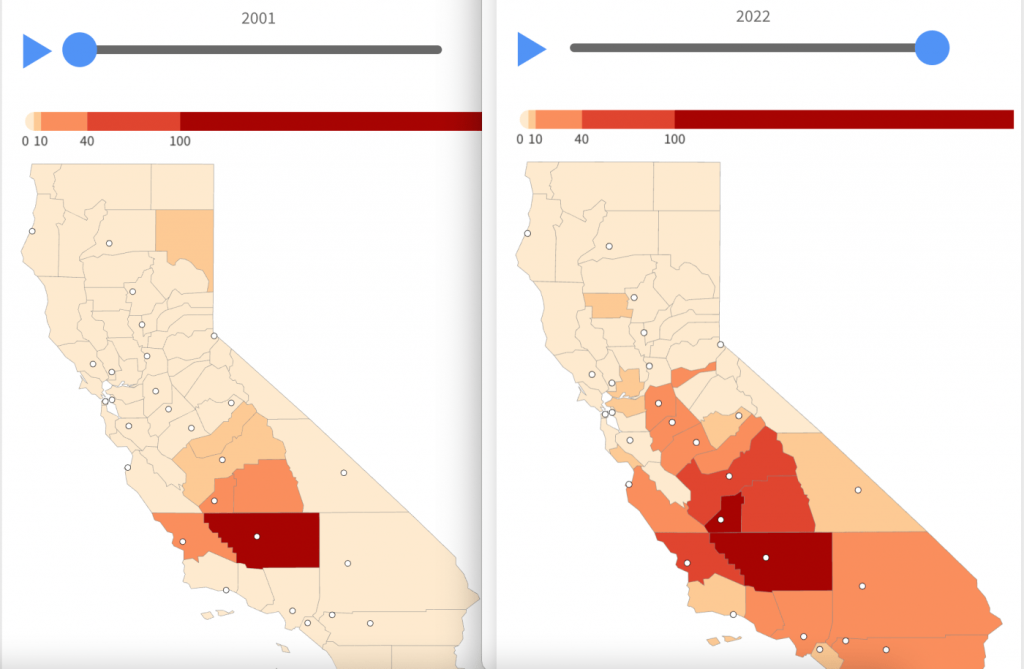

Despite its growing footprint, the fungus continues to be concentrated in the southern part of California’s Central Valley and through the Central Coast. Even parts of the greater Bay Area also have some of the fungus locally.

The illness can be hard to distinguish from other respiratory illnesses, like influenza and COVID — one reason educating the public and health care providers is so important to Johnson. While health care providers in Kern County might be familiar with the illness, providers elsewhere might not. “The trick is the diagnosis… and the uninitiated have great trouble making this diagnosis,” said Johnson, one of the preeminent experts on the disease. Once identified, there are several treatments that can help patients recover, but it often goes undiagnosed.

Earlier this year, a group of cases tied to the Lightning in a Bottle music festival in Bakersfield this summer brought the illness to headlines and local newscasts, which warned attendees to be on the lookout for symptoms.

While the highest per capita rates of the illness happen in Kern, Kings and San Luis Obispo counties, even residents of San Jose and San Francisco are not completely spared from the virus, which can travel up to 70 miles, according to Johnson. “There’s quite a significant amount of cocci within a few miles of where you are, if you’re sitting in San Jose,” he said.

And while the illness is more likely to make vulnerable people seriously ill, the young and healthy are not immune. Many cases of Valley fever have been identified among members of the military, and at state penitentiaries in the region where the fungus is endemic. Even marine life is not immune, with some cases identified in sea otters. “And none of them drove to Bakersfield, I promise,” Johnson said, emphasizing that the fungus is widespread.

While there are annual fluctuations, and occasional spikes in the number of cases, there has been a clear upward trend in the past two decades, with more and more cases identified each year. And it’s not because health care providers are getting better at diagnosing it, though that might be a factor, Johnson said.

Johnson said even in Kern County, which has a higher rate and more cases than any other county in the state, he says he is the only doctor that sees children diagnosed with Valley fever. “I have a very large number of children with cocci this year, way more than I’ve ever seen before,” Johnson said.