If California’s population is well off its peak, and developers keep on building housing, why does the cost of living in the Golden State remain lofty?

My trusty spreadsheet looked at fresh demographic figures from the state Department of Finance to find any hints of solving this housing riddle.

Related Articles

California’s great exodus finally slows as population increases after 3-year decline

Austin’s Texas glow Is fading as home prices drop, office vacancies rise

Skelton: California’s budget relies on richest taxpayers and we’re paying the price

2 California cities make list of ’50 best places to live in US’

The US was getting too expensive. So this California artist relocated to France for a slower-paced life

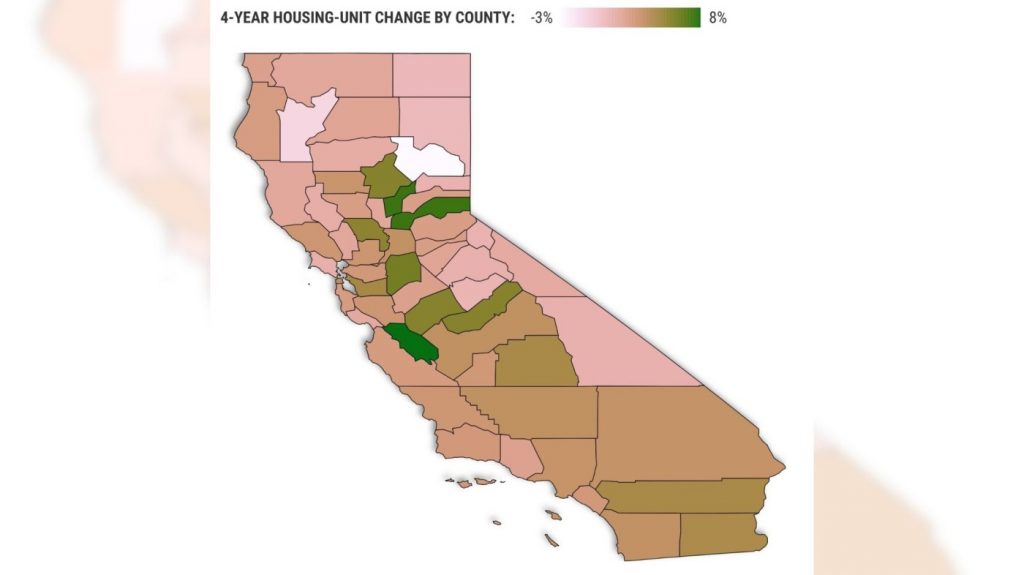

Start with the basics: California had 38.2 million residents living in households last year – that’s down 375,800 since 2020, or a 0.9% loss. In the same timeframe, California’s housing stock grew to 14.8 million residences – a 432,700 improvement since 2020, or 3% growth.

How did that translate to folks seeking homeownership or an apartment?

Well, the median-priced California home got 25% more expensive since 2020, according to the California Association of Realtors. Meanwhile, typical rents in 12 Golden State metropolitan areas averaged 24% hikes, says Zillow data.

So, seemingly favorable demographic trends for more affordable living didn’t create any California housing bargains. It seems other economic influences were busy boosting housing expenses.

Cheap mortgages were followed by expensive ones. Investors hungry for yields kept housing demand high. And developers remained thirsty for luxury living.

Plus, bosses desperate for workers kept unemployment low. More paychecks, more housing demand. And don’t forget inflation – and fatter wages, too.

New stuff

Peek at what types of homes were added to the Golden State’s residential stock, mostly the pricier options: houses and apartment complexes …

Single-family homes: Up 184,000 since 2020 or 2.2%.

Rentals, five or more units: Up 182,500 units since 2020 or 5.3%.

Attached homes: Up 34,500 condos since 2020 or 3.3%.

Rentals, two to four units: Up 26,000 units since 2020 or 2.3%

Mobile homes: Up 5,600 since 2020 or 1%.

What was roughly a split in creation between ownership opportunities and rentals didn’t push the affordability needle in either direction.

What’s used

Next, let’s think about a big challenge – empty housing.

This housing wrinkle can be tied to everything from the business challenges of renting housing to inefficiencies in selling homes and what second-home ownership does to supply.

California had 13.9 million occupied residences last year – up 405,000 since 2020 or a 3% gain. But ponder vacant homes – 944,500 last year, up 28,000 since 2020, also a 3% gain. This growth in unused housing equals roughly 6% of what was created since 2020.

So despite all the chatter about a housing “shortage,” the statewide vacancy rate — 6.37% last year from 6.46% in 2020 — barely changed, at least by this math.

Yes, there’s been various ideas tossed about how to trim vacancies – including taxing owners for empty housing. But vacancies are a reality of a California marketplace with the most rentals in the nation – and some of the best locales for vacation homes on the globe.

How it’s used

What’s not talked about much is how Californians reacted to the new supply of housing: fewer people in homes.

The average number of Californians living in an occupied housing unit was 2.75 last year – that’s down from 2.86 in 2020. That’s not an insignificant change across 39 million residents.

Why did it occur? There’s the pandemic effect of people wanting larger living quarters, often shunning roommates. Others got historically cheap mortgages in 2021-22 and won’t move, no matter how oversized their residence is for their needs.

Some of this trend may be adult children leaving the parents’ home – with destinations both in and out of state. Young families frequently exited for other states, too. Or it’s older residents losing a spouse.

No matter the cause, smaller households gobble up housing supply.

My spreadsheet tells me that the drop in California’s household density equals demand for 131,000 housing units. So one can argue that roughly one-third of the housing created since 2020 went toward giving Californians more space to live.

Yes, less-dense housing can be a societal plus. But it comes with a cost – a drain on the housing supply.

Jonathan Lansner is the business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at [email protected]