From the driver’s seat of his parked truck, Lewis recalled what it felt like to take opioids.

He was prescribed Vicodin after getting his wisdom teeth removed at age 15, he says, which jumpstarted an addiction he’s battled for nearly two decades. (Lewis’ last name has been omitted for concerns regarding his medical privacy.)

“I just remember it took all the worries away,” said the Pennsylvania native during a September interview over Zoom. “It gave me a feeling almost like I didn’t have to be afraid.”

He eventually started experimenting with stronger opiates, namely Percocet and Oxycontin, and progressed to heroin a couple years later. He said it was “the worst decision” he’s ever made.

“I lost everything,” said Lewis, who is in his early thirties.

In recovery since 2021, he credits a virtual telemedicine business, Ophelia, with helping him get back on track: “It’s literally changed my life,” he said.

Ophelia partnered with Highmark Wholecare last March to provide telehealth addiction services to its patients, which includes Pennsylvania-based Medicaid and Medicare members; in April, it was designated as Pennsylvania’s first virtual Center of Excellence for opioid use disorder. Centers of Excellence are designated treatment centers deemed official by the state Department of Human Services.

Ophelia is now in the company of other local Centers of Excellence that offer telehealth services for opioid use disorder, including JADE Wellness Center on the South Side and Gateway Rehabilitation Center in Greentree.

These moves signal the increasing popularity telehealth services have enjoyed since the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when options expanded to allow for virtual prescribing of controlled substances.

Many in the larger population choose telemedicine for its convenience; for those with opioid use disorder, being able to acquire medication to treat the condition in a discreet and efficient manner has been improving retention rates and reducing stigma around addiction.

But this policy is at risk of termination. With the U.S. public health emergency status from the pandemic having ended last May, exceptions that allowed prescribing of controlled substances over telehealth were no longer guaranteed. That program has been extended twice now by the Drug Enforcement Administration and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The current extension goes through Dec. 31.

“At the federal level, there’s great support” for telehealth, said Wilson Compton, deputy director of the National Institutes on Drug Abuse. “Whether this can continue is not clear.”

Lakshmi Reddy, chief medical officer of Highmark Wholecare, said the statewide partnership with Ophelia will be a great way to provide treatment options for patients with substance use disorder, and to break down stigma.

“This is going to be lifesaving,” said Reddy. “A significant amount of our membership has a substance use disorder, and they need treatment for it.”

Among the benefits of telehealth are potential barriers to in-person appointments, such as needing to secure transportation and childcare, as well as scheduling around a job.

Patients often connect when they’re on a lunch break, noted Allison Berneking, Lewis’ clinician and Ophelia’s regional clinical director. Lewis, who lives in Lackawanna County, often took calls while walking through the countryside, she said.

Many patients, like Lewis, started using the virtual platform simply because they didn’t have other options, said Berneking. Lewis discovered Ophelia through a Facebook ad in 2021, which he almost scrolled past. He said he had tried everything — rehab, suboxone clinics, Alcoholics Anonymous — but he always returned to using.

“At this point, I just wanted to stop everything. I needed a different kind of change.”

And at the time he became a patient, he didn’t have a car to drive to a clinic.

“If someone takes three buses to get to a health care appointment, missing just one bus might mean you miss the appointment, and that could lead to a relapse,” said Reddy. “We want our members with substance use disorders to feel they have options.”

Compton, of NIDA, noted that even within city limits, transportation can be cumbersome — and with a condition like opioid use disorder, desire for treatment can waver greatly depending on someone’s mood, environment or access to substances.

Jody Glance, medical director of addiction medicine services for UPMC Western Behavioral Health, also conducts telehealth services for people with substance use disorders, and has seen benefits from the approach.

“Some people we treat deal with debilitating chronic pain, and it’s hard for them to get to the clinic,” she said. “This is the group I think is helped the most (by telehealth).”

Telemedicine allows the system to catch patients sooner and initiate care, instead of them being placed on a monthslong waiting list, or being referred to a specialist, leading to further hurdles. Berneking takes patients while they’re folding laundry, watching their kids or using the Wi-Fi at the public library.

This kind of intimate peek into a patient’s life can strengthen doctor-patient relationships. Berneking noted times that general contractor patients excitedly showed her the structure they were building, or times she’s met children on-screen.

“People start to open up and become more vulnerable when they feel safe,” she said.

Glance echoed this sentiment. She will sometimes inquire about art hanging on the walls behind her patient, such as one with a passion for photography.

“We’ve been able to talk with patients about things that might not otherwise come up if the visit was not at home,” she said. “You get to know more about their personal life outside of what they might bring into the doctor’s office.”

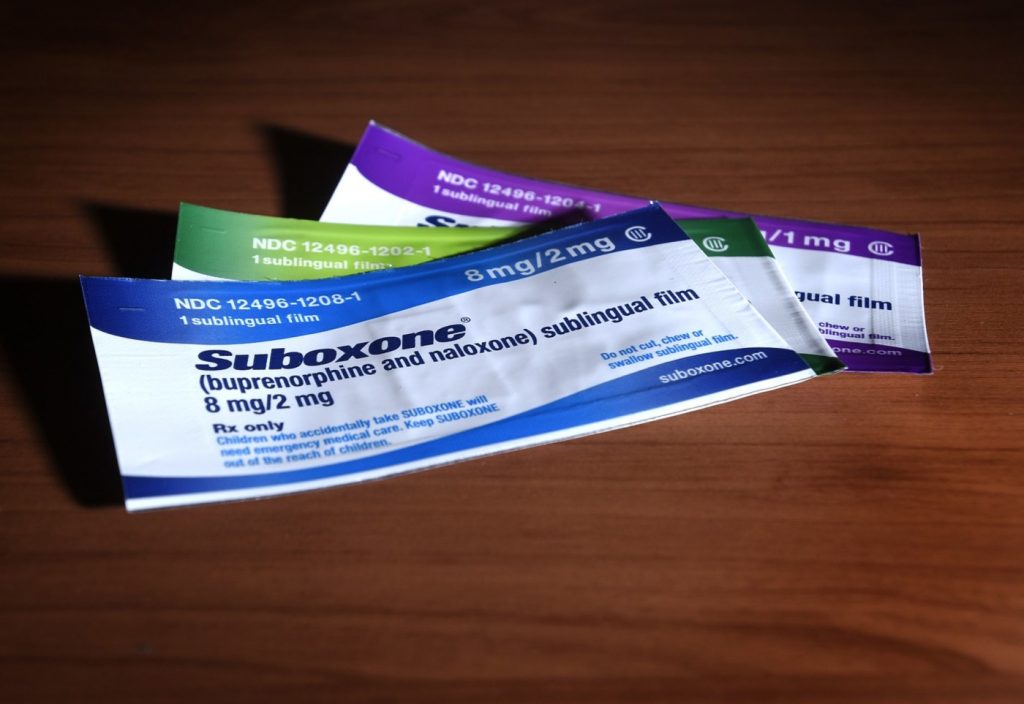

Both Glance and Berneking said they’ve noticed that no-show rates have decreased, retention rates have increased, and patients have become more engaged through telehealth visits, which has been backed by research. This could mean the difference between someone who relapses and doesn’t seek treatment, and someone who is prescribed Suboxone — like Lewis — and becomes sober.

“It’s been great, the fact that I can take my calls or my meetings via Zoom,” said Lewis. “That’s huge for people — being able to be in the comfort of your own home, or not having to call off work to go to a doctor’s appointment. That’s kind of what held me back. I didn’t want to have to take off work.”

Telehealth has its drawbacks, though, especially as a burgeoning technology that only started to see widespread use because of the pandemic. (Compton called it a “natural experiment.”)

For one, patients must have access to the internet and a device to conduct the appointment on.

Berneking said this hasn’t been a significant issue in her practice — even people who are homeless often have smartphones and can use the Internet at a friend’s house, library or coffee shop. Highmark Wholecare is taking steps to increase rural access to broadband to address this issue by working to secure state grant funding, said Reddy.

The most significant barrier to successful prescribing of medication for opioid use disorder through telehealth has actually been stigma, say some providers.

“Not all pharmacies are willing to fill (prescriptions) through telemedicine,” said Compton.

Despite these barriers, telehealth providers recognize the benefit to their patients — and the risk of ceasing the option.

More than 200 organizations, including UPMC Health System, signed a letter to DEA Administrator Anne Milgram in April, urging the institutions to update its proposed rules and encourage pharmacies to continue this method of prescribing past Dec. 31.

“Telehealth services allow timely access to treatment for more patients, during a time when there is a shortage of health care providers across the country and there is great need, especially among rural and underserved communities,” said Noreen Fredrick, vice president of ambulatory and community behavioral health services for UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital, in a statement about why it signed the letter. “Ending current flexible regulations would create barriers for many patients and significantly impact care delivery and treatment services.”

Telehealth has also normalized treatment for addiction alongside other health care services, said Glance, helping to combat stigma.

“We all moved into the virtual care space at the same time,” she said. “We could see a patient for asthma and then for opioid use disorder.”

Yet there are times an in-person visit is warranted, and seeing a doctor only through a screen may prevent important full-scale workups. Bloodwork, physical exams or vitals testing such as blood pressure can inform physicians about a patient’s condition, a missed opportunity during a virtual visit.

For Lewis, he’s transitioned from weekly visits with Berneking to monthly ones. He bought the truck he gave the September interview in, and he’s now working in construction.

“I truly think that working with Ophelia gave me th(ese) opportunit(ies),” he said. “It’s something small to other people, but that’s a huge milestone for me personally. I often think about if I just kept scrolling past that post, then I probably wouldn’t have a car. I probably wouldn’t have a job. Things would be different.”

___

(c)2024 the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Visit the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette at www.post-gazette.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.