California housing regulators are demanding that cities statewide develop meticulous plans to add 2.5 million affordable and market-rate homes by the end of the decade — but some local officials say the process sets them up for failure.

Frustrated Bay Area mayors and city councilmembers say the new planning requirements are needlessly confusing and that regulators have been slow to review the plans that have been submitted. They argue the convoluted process is leaving some cities vulnerable to unfair penalties for failing to get state approval.

Auditors will now examine whether the state is doing enough to help local governments satisfy the requirements and plan for many more homes than ever before.

“We do have an affordable housing crisis, and the vast majority of cities are doing their best effort to help, but there has been inconsistent guidance,” said state Sen. Steve Glazer, a Democrat from Orinda. He’s pushed for some new housing laws and programs but he has received mixed reviews from housing advocates.

In a letter to the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, which approved the audit last week, Glazer wrote the complaints he’s received from cities — which he declined to identify because they have not all received approval for their proposals — point to “structural problems” in how the state reviews the every-eight-year plans, dubbed “housing elements.” While the audit will not be legally binding, he hopes it can “reveal the sources of these problems and how to cure them for current and future review processes.”

A 2022 audit of how the state sets goals for the number of homes different regions are expected to approve found errors in the process, which may have led regulators to underestimate the housing need in some areas and overestimate it in others. While the state completed some of the audit’s recommendations for calculating future housing goals, the review did not force any legislative reforms.

Ahead of the new audit, Glazer raised concerns that cities still waiting to get approval are now subject to penalties such as losing state funding, less time to complete mandatory zoning reforms and the dreaded “builder’s remedy,” which could force local officials to accept massive housing projects.

More than a year after Bay Area cities and counties were supposed to finalize their plans, almost 30% have still yet to get state approval. Most are smaller cities that haven’t received much scrutiny on past plans. San Francisco and Oakland won approval shortly after last year’s Jan. 31 deadline. San Jose didn’t get approval until the start of 2024.

Pleasanton Vice Mayor Julie Testa, a vocal critic of the state’s push to build, said the 32 Bay Area jurisdictions without compliant plans are evidence of serious flaws in the review process. Testa said that before Pleasanton received approval last summer, it was sometimes difficult to get a timely response from reviewers. She said local planners were often left guessing how to meet the housing element requirements.

“It is absolutely a moving target,” Testa said.

Meanwhile, housing advocates said that as recent laws made the planning process more stringent, state and regional officials alerted cities about the new requirements while offering additional training and other resources.

“Many cities ignored it and just thought they were going to do the same thing they’ve always done,” said Mathew Reed, director of policy with the Silicon Valley pro-housing group SV@Home. He said a backlog of half-baked housing element drafts for regulators to review likely contributed to delayed review times.

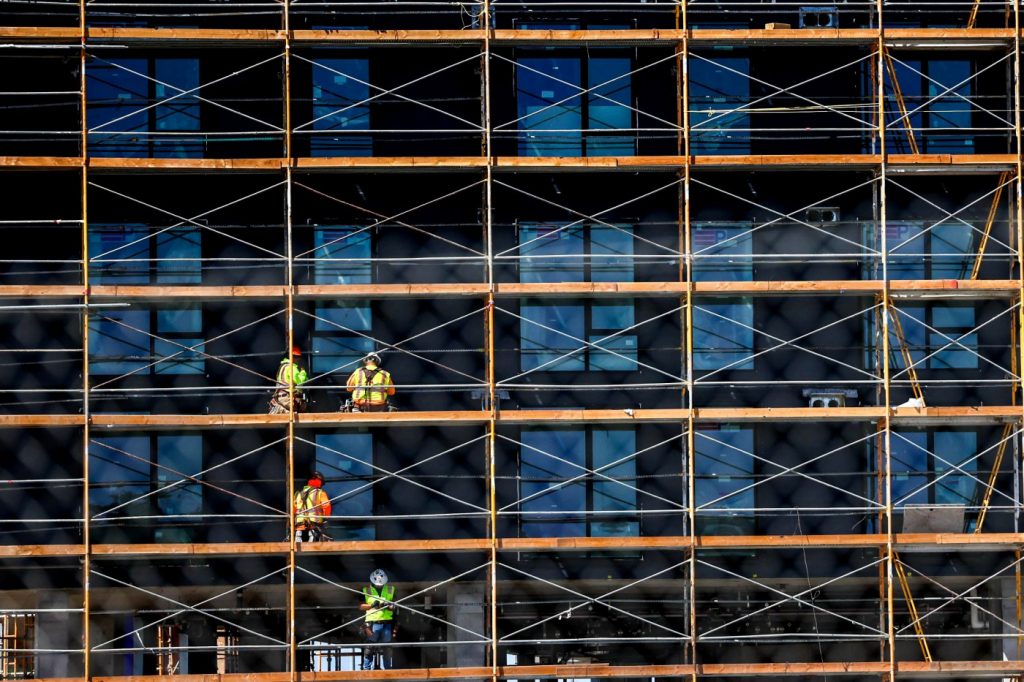

For its part, the Department of Housing and Community Development said in a statement that it’s proud of its work to “ensure that communities plan for their fair share of housing.” It took credit for an increase in homebuilding in recent years, though high interest rates and other economic factors have since stalled new construction.

Related Articles

5 charts that show which Bay Area cities are building the most housing

Bay Area building boom is reaching an end, may be years before it returns

San Mateo County to launch mental health ‘CARE Court’ to bring homeless people off street

Editorial: In Berkeley, elect Hernández Story for vacant council seat

Santa Cruz County a case study on pandemic Project Roomkey

Every eight years since 1969, the department has required cities and counties to submit housing plans that describe how to accommodate a specific number of single-family homes, condos and apartments across a range of affordability levels. But during recent cycles, most jurisdictions haven’t come close to hitting their low- and middle-income housing goals.

To help reverse that trend, the state is now asking local officials to do much more meticulous planning to meet their latest housing targets, which in some cases are double that of the previous cycle. That includes proving sites identified for future homes have a realistic chance of development and providing specifics on programs to streamline the local permitting process.

In 2021, the state also created its Housing Accountability Unit to crack down on local officials skirting state housing laws and flouting the planning process. Last year, the unit and the state attorney general sued Huntington Beach for failing to develop a housing element. In March, a judge stripped the city of some of its authority to block new housing projects.

The newly approved audit is set to begin this fall, but it’s unclear when it could be finalized. A high-profile audit of the state’s homelessness spending released last month took more than a year to complete.