Federal scientists are closely studying H5N1 genetic sequences from California dairy workers in search of any dangerous mutations that may make the virus, called avian flu or bird flu, more skilled at jumping from animals to people — then spreading.

“It can tell us how the virus is evolving,” said Stanford infectious disease expert Dr. Abraar Karan. “It is a window into what is going on.”

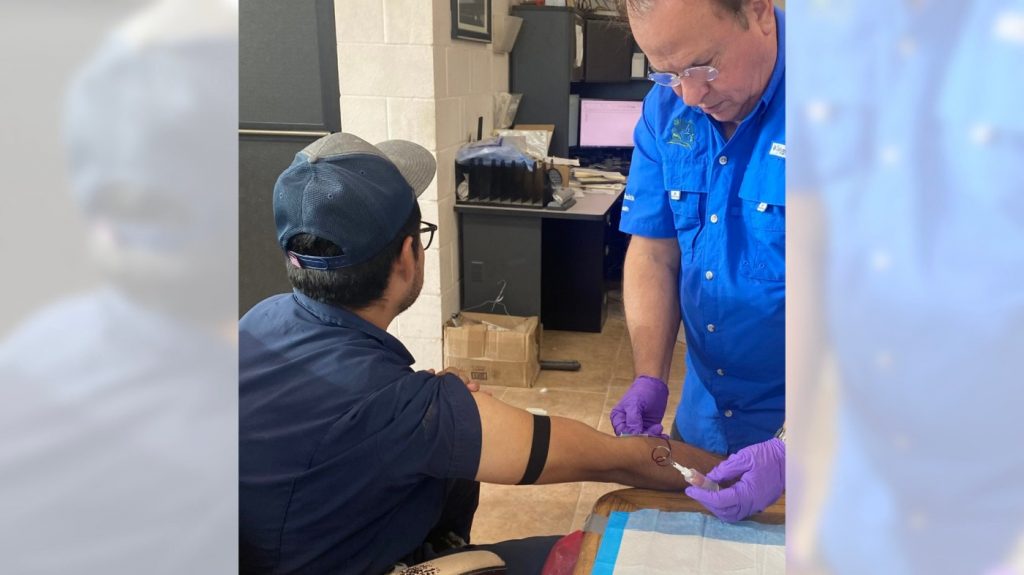

Samples of the virus were obtained by swabbing two patients with the state’s first known human cases of avian flu, confirmed by the California Department of Public Health on Thursday. While the patients’ locations were not disclosed, their illnesses are unrelated to each other. They were sickened independently after exposure to cows, not spread from person-to-person. The risk to the public continues to be low.

Both cases were mild and with little or no respiratory symptoms. The main complaint was a common eye inflammation called conjunctivitis, caused by workers not wearing adequate eye protection while working with infected cattle. The virus latches onto cells in the membrane that lines the eye.

Samples of the California virus have been sent to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, which is genetically deciphering them. The work is a challenge, however, because samples often contain very low levels of active viral RNA, the molecule in which flu genomes are written.

By comparing the samples to each other and other samples in the U.S., scientists can detect whether the virus is mutating in a way that will make it more likely to infect other humans.

If so, this increases the risk of it sweeping through the population, potentially triggering a dangerous outbreak.

The same sequencing technology is the key tool in identifying and tracking the emergence of new SARS-CoV2 variants, a realm of work called “genomic epidemiology.” With widespread use during the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become easier, quicker and more ubiqutious, proving itself as one of the most important innovations of the 21st century.

H5N1, just like our more familiar flu viruses, constantly changes as it multiplies and diversifies. Viruses are engaged in an evolutionary arms race — as the immune system makes new antibodies, the virus develops new mutations.

Each iteration seeks to offer some sort of advantage, such as an ability to sidestep the immune system or extreme contagiousness.

Viruses shift in small, but sometimes large, ways. It is not yet known which genetic changes would allow H5N1 to better infect humans, or become airborne.

“As this happens, the virus itself gains mutations that can change how dangerous it is,” Karan said. “These changes are ones that we need to be aware of.”

Genetic sequencing will also help ensure that future vaccines and antiviral drugs are a good “fit” and will be protective.

To fend off an outbreak, on Thursday the federal government’s Center for the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, announced that it is providing about $72 million to four pharmacuetical companies — CSL Seqirus, Sanofi, and GSK — to take the next steps in H5N1 vaccine manufacturing. The vaccines, now in bulk storage, will be moved into ready-to-use vials or pre-filled syringes for human immunization, so that they are ready for distribution.

“As infections in domesticated animals continue to spread, the risk for human infection could rise,” said BARDA Director Gary Disbrow. “In an abundance of caution, we are taking steps to increase the amount of vaccine that could be immediately available if needed.”

The virus has already significantly changed since first identified in geese in 1996. In 2020, a new, highly pathogenic form emerged in Europe and spread quickly around the world. In the U.S. it has affected more than 100 million farmed birds, the worst bird flu outbreak in the nation’s history.

New mutations have eased its spread from birds into multiple other species, including humans. It has been detected in wild animals like bears, foxes, seals, and skunks, domestic animals like cats and dogs, and zoo animals like tigers and leopards. Even marine mammals, like harbor seals, gray seals, and bottle-nosed dolphins, can become infected.

The climbing case counts among cows on California dairies — jumping from 3 to 56 infected herds in less than a month — worry epidemiologists and health experts, who are monitoring farm workers.

Since March, when the H5N1 virus was first detected in U.S. dairy cattle, there have been more than a dozen cases of human infection that were traced back to contact with infected animals.

An early genomic analysis by the CDC found minor differences between people, cattle and bird versions of the virus.

In humans, there was one genetic change — a mutation called PB2 E67K — that has a known link to virus adaptation to mammalian hosts. Scientists emphasized that this hasn’t been linked to virulence or rapid transmission.

Mutations may explain clinical symptoms — why, for instance, the virus seems to affect a person’s eyes more than the upper respiratory tract, like other flu viruses.

One case, reported in Missouri on Sept. 6, is getting special attention. That’s because investigators found no link to livestock or unprocessed food products, such as raw milk.

Jürgen Richt, a veterinary virologist at Kansas State University in Manhattan, called it “a mystery case.”

“So you have to throw your net a little wider,” he told the journal Nature. “Maybe they cleaned out a bird feeder in the household. Did they go to a state fair? What kind of food did they consume?”

On September 13, the CDC announced that two people who had close contact with the infected person had also become ill around the same time. One of them was not tested for flu; the other tested negative.

Meanwhile, researchers are combing through that patient’s patchy genome-sequence data from virus samples — and will compare it to the California cases and other samples.

The two California cases “are not, by themselves, a cause for increased concern for pandemic risk,” according to John Korslund, a retired U.S. Department of Agriculture veterinarian epidemiologist, who studies livestock diseases.

“But each case is still each important on its own,” he said, “because any one of them could signal trends towards viral adaptation for human-to-human spread.”