When Francis Ford Coppola was at his frenzied peak, he created astonishing worlds onscreen. Offscreen, he was intent on doing the same, striving to build a utopian creative community with his American Zoetrope and Zoetrope Studios.

While pushing boundaries and challenging conventions, however, Coppola spread himself thin, which undermined his vast ambitions. For a long time, however, he came out on top with films including “The Godfather,” “The Godfather II,” “The Conversation” and “Apocalypse Now.”

Until he didn’t.

The failure of his 1981 film “One from the Heart,” a musical romance with Teri Garr, Frederic Forrest, Raul Julia and Nastassja Kinski, was heartbreaking for Coppola not just because the movie bombed but also because its financial failure undermined his dreams to revolutionize Hollywood and make a home for creative artists.

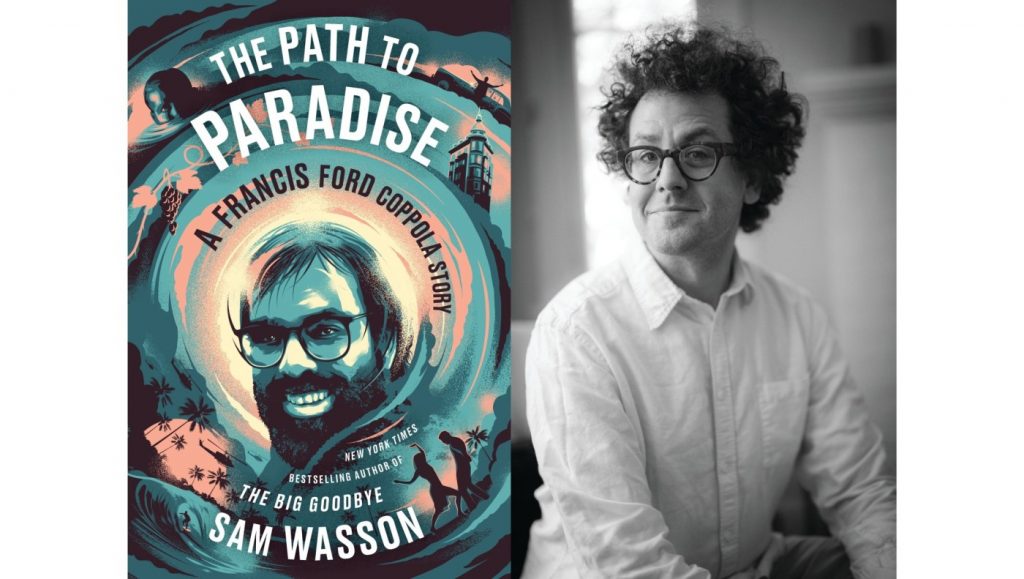

Sam Wasson’s “The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story” isn’t a full-on biography of the director. Wasson forgoes deep dives into later films like “Tucker: The Man and His Dream” and “The Rainmaker,” instead focusing on the films “Apocalypse Now,” “One Through the Heart” and the forthcoming “Megalopolis” to show Coppola’s mighty struggles on and offscreen. (The book also touches on Coppola’s bipolar disorder and its impact on his life and his work.)

Wasson, whose previous titles include “The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood,” spoke recently by video from his home in Laurel Canyon about the book and the man himself.

Q. Why tell this narrowly focused story for a man with such a long and varied career?

Most writers misconstrue him. The deepest part of his soul is [his studio] Zoetrope, so I wanted to position that at the center of Francis’s spirit. And that’s a shorter book because there’s a whole phase of his life where Francis is not making Zoetrope work. After his studio goes down, he’s a director for hire a lot of the time. That’s the story of his life, but it’s not the story of his soul.

Q. It’s ironic to write a concise, contained book about Coppola, his movies and his studio. He’s all about the epic saga.

Well, my process was not contained – if they made a documentary about me writing the book, it might look like [the warts-and-all “Apocalypse Now” documentary] “Hearts of Darkness.”

Q. You were living in the jungle of your own mind, to place this in an “Apocalypse Now” landscape.

Absolutely. Even nonfiction is not going to be any good if the unconscious is not in it. If you just stay in the literal, you’re not going to make something with the power of great storytelling. And so you have to go into whatever your jungle is.

I was changed by this book. Although, of course, I had the experience of sitting alone in my house and it’s beautiful out and I can go out to dinner with friends. I love writing about filmmakers like Francis because they have to control all of the external and internal elements and that’s thrilling to watch.

Q. How much of his work was enthusiastic idealism, how much was self-indulgent ego, how much was artistic genius driven by insecurity, and how much was bipolar behavior?

I don’t see any ego or megalomania in Francis. He was too far ahead of his time with new technology and he was trying to do too much at once, and because of that it all crumbled. But the story has been told incorrectly, as if this was a function of his megalomania. But it’s really a function of his ambition. It was one of the reasons I wrote this book, to correct that misconception.

I think to have a large vision and go for it is about as beautiful a thing a person can do. He was not just trying to create the best work he could, but to create the best community to foster that kind of work. Trying to change the world is a huge ambition but I see that as super-heroic, not selfish.

How much is neurochemistry? It would take an MD to tell you exactly how much, but we know that’s definitely in the conversation. Still, it’s all coming from a pure and beautiful place.

Q. His expansive vision and unbridled passion made him Midas in the 1970s while making dark movies about people with limited vision and warped passions. Then he tried making a movie about love and it bombed. Why?

“One From the Heart” is more remote for him. I think I said in the book that love was the real apocalypse for Francis. It’s something he hadn’t figured out. Eleanor [his wife of 60 years, whom he had cheated on during the filming of “Apocalypse Now”] had distanced herself for good reasons. Maybe he needed to make peace with that before he started filming. I find the story so touching partly because Francis made movies not just to tell a story but to live that story. And this was his attempt at healing, but he was not truly in a love frame of mind.

Q. How much did “One From the Heart” suffer from his struggles with love and how much was it the use of new technology that often had him directing the film remotely in a trailer? Or are those two connected?

You just answered it exactly. He is stepping away literally from the actors and from the emotional core of that movie. That movie has a lot going for it, but the passion between the characters is not one of those things. The passion for filmmaking is there but it didn’t do well because the human part is not there. And Francis ran from that into his remote world of the audio video control vehicle and what he was calling live cinema.

But “One from the Heart” was not what Zoetrope was about — so much of Francis’ work and life is about the process. It’s not about the product. What’s happened though is that he’s made some incredible product so people have misunderstood him as the artist first. I really see him as a visionary first, artist second.

Related Articles

Bay Area arts: 12 shows and exhibits to see this weekend

What to watch: Strange, miraculous ‘Monster’ one of year’s best films

Tom Cruise seen making out with daughter of Putin ally and ex-wife of oligarch: report

Oprah Winfrey was more than OK with Drew Barrymore’s ‘cringey’ caress

Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘shared family’ tragedy with Ryan O’Neal involved their sons

I think Francis sees himself as the conductor of the symphony, the man who brings the elements together, the man who sets the table. He says he’s not a director first, that there are natural directors like Scorsese and Spielberg. Francis has to work hard at it, but what comes naturally to him is community building.

Q. If someone was going to make a movie called “Coppola: The Man and His Dream,” who would play him?

Brad Pitt.

Q. Really?

You want to get this made, don’t you?

Q. But who else?

He’s got to have an imposing physical presence.

Q. A young Orson Welles?

That’s a good one. Like with Francis, you could see the horizon in his eyes.